Erato Ioannou är en cypriotisk författare som jag läste i somras. Efter min recension av hennes novell Something tiny, fick vi kontakt på Facebook och då föddes idén om en intervju här på bloggen. I samråd med henne publicerar jag intervjun på engelska, vilket jag hoppas att ni har överseende med.

Om Erato Ioannou

Erato Ioannou skriver noveller och hennes första novellsamling Cats Have it All gavs ut 2004 (Armida book). Efter det har hennes noveller publicerats i tidskrifter och antologier över hela världen. Nyligen var hennes novell Deserted med på korta listan för 2019 års Commonwealth Short Story Prize. Hon är assisterande chefredaktör på In Focus, cypriotiska PENs tidning. Hon är också grundare av Room for Art, ett initiativ för att stödja konst och konstnärer på och utanför Cypern. Hon bor i Nicosia med sin man, deras två barn och flera katter. Läs mer på hennes webbplats.

Interview with Erato Ioannou

I am interested in how the literature scene looks like in Cyprus. Would you say there are many local writers in Cypriot bookstores?

During the last decade, the literary scene in Cyprus is buzzing. An increasing number of people use writing as a means of artistic expression. The Writers’ Union of Cyprus, one of the largest of the writers’ unions on the island, consists of approximately 250 members from both sides of the divide, a significant number, given the size and the population of the island.

One can certainly find books by Cypriot writers in local bookstores as well as in bookstores in Greece. However, there are very few opportunities for Cypriot writers to forge links with publishers outside Cyprus and audiences from around the world.

I have read you and Nora Nadjarian, are there any other contemporary writers who have been translated to other languages?

Both Nora and I write directly in English. I could say that today, English is the lingua franca of international literature if you are to count the number of books published in English and the number of books published in other languages. Writing directly in English or having literary work translated in other languages makes it available to a wider audience. Cyprus government has a grant scheme for subsidizing the translation of literary work by Cypriot authors, into any foreign language, which has already been published in the original language (Greek). This is a good step to help put Cypriot writers on the international literary scene, but unfortunately, this grant scheme excludes Cypriot writers who write in other languages like, for example, English and Turkish.

You are a female writer. Would you say it is harder to be a female writer than a male writer?

During those early clumsy attempts to write creatively … I must have been around twelve years old … all my protagonists were boys (!). I guess this was because all the literature that I had been exposed to, by that time, was male-dominated—both in terms of authors and in terms of characters. Tom Sower and Huckleberry Finn were ‘cool’ and adventurous and I wanted to write ‘cool’ and adventurous characters. Boy meant cool. Isn’t this messed up? Truth is, there weren’t any powerful, dynamic, girl characters around. At least I didn’t have the chance, back then, nor was I urged or directed to read any of them, if there were any. I suppose the first step toward women’s literary emancipation is acknowledging the fact that literature, up until the 70s or the 80s had been male-dominated.

The Brontë Sisters published their work under male pen names. The debate between literary scholars on whether Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein herself or with the ‘help’ of her husband carries on! And even today, we have the example of Joanne Rowling who was urged by her publisher to use the genderless J.K. Rowling! Instances of how women writers’ voices and women writers’ identities have been oppressed, their talent and abilities questioned through the centuries, are inexhaustible.

Recently, I received the following comment about my work: ‘So, you’re writing women’s fiction.’ I was taken aback because automatically my writing was judged solely on the basis of my gender and my characters’ gender. It’s as if there is ‘writing’ and ‘women’s writing.’ I’ve never heard such a thing as ‘men’s writing.’ So, writing by men is the norm and writing by women is the ‘other?’

In this sense, to answer your question, it’s not an easy ride.

Is there a feminist movement in Cyprus, and can you see it in Cypriot literature?

The global feminist movements of the 1960s saw no participation on behalf of Cypriot women. During that time, women of Cyprus were experiencing the turmoil of intercommunal violence and afterward the suffering of the Turkish military invasion of the island in 1974 and its tragic repercussions.

In a traditionally male-dominated, patriarchal society, which marginalized women for decades after the first feminist movements appeared around the world, women of Cyprus today have moved ahead in regard to education and employment. However, decision making bodies like the Council of Representatives and the Council of Ministers are still male-dominated. The attempts to mainstream gender in decision-making bodies are weak and have not shown results as of yet. Through their civil society organizations, women are raising their voices on social issues and most importantly on women’s issues and needs that have been ignored.

Women today have empowered themselves to challenge patriarchal structures and make their presence visible. But there is a long way to go.

And, indeed, since writers are inspired, affected by, and explore, the world around them through their writing, gender issues are reflected in Cypriot literature especially in literature written by women.

I also have to ask you, is there a special “Greek” style in writing? I have read a Greek short story collection, and there was a humoristic tone in all the stories I read. I found the same in yours. Would you say there is a special way of writing tradition in the Greek language?

I think that there are as many styles as there are writers. Inevitably, a writer’s work is affected both thematically and stylistically by her immediate surroundings, by her social environment, and the historical context of the times. In the same manner, a writer may consciously choose to accept or consciously choose to resist influences by other authors. One way or the other—acceptance or resistance—will inevitably mold one’s work. I firmly believe that whatever we read affects our writing at a deeper subconscious level. Maybe in the past such a thing as a national literary legacy, in terms of themes and style, within geographic or linguistic locales, did exist. Today, however, thanks to technology and translation, world literature with its abundance of themes, traits, backgrounds, is at our fingertips. Each of us, with our own individual literary voice, is part of a massive new literary epoch characterized by diversity.

As for the use of humor in my writing … I would say that the themes around which my writing revolves are loss and constant yearning. Fiction provides a limitless space to negotiate these themes which characterize the absurdity of our world today. My characters deal with extreme situations and they resort to extreme action. Comical twists heighten their tragedies.

You live in a divided country. Is there any contact between writers in spite of the divide? If yes, what kind of contact?

Absolutely. Art is a powerful tool for mutual understanding and reconciliation.

The results of the Turkish military invasion on the island in 1974 have inflicted deep wounds on all Cypriots. Inherited trauma has been haunting us all—on both sides of the divide. It has left its mark on our literary work. Violence is still present in our memories even in the memories of those born after the war. It is present in its physical form—in the line separating the island. It has marked the souls of the refugees, the lives of those who lost their loved ones, their homes.

Interactions between writers from all over the island are enhanced through various literary projects and events such as readings, book presentations, open mics, festivals, and workshops. Bilingual short story and poetry anthologies were published featuring writers from both sides of the divide.

What are you working on now?

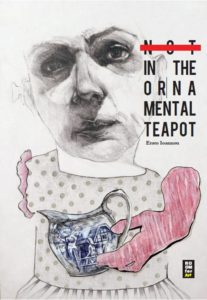

My short story collection Not in the Ornamental Teapot will be out by the end of September 2020, and soon after that, it is going to be published in Greek. The collection features strong-minded and audacious heroines who challenge and deconstruct the roles assigned to them by dominant narratives and preconceptions.

Concurrently, I am putting together a writer’s residency program via Room for Art, a civil society organization which aspires to provide support and guidance to local and international writers and artists, who juggle the demands of ‘real life’ and their creative work.

Also, we are gearing up for the new school year, amidst Covid-19. My son is going to high school and my daughter is going to fifth grade.

And, a new cat has adopted our family.

There are a lot of exciting plans. Hopefully, the rest of 2020 will behave itself.

Kjell Westö har jag fått tips om när det kommer till män som ifrågasätter mansrollen. Jag älskade hans bok Hägring 38 och när mina bokcirkelkompisar ville läsa hans helt nya Tritonus, var jag inte sen att haka på. Boken är utgiven på Förlaget och här i Sverige på Albert Bonniers förlag. Jag lyssnade på Kjell Westös egen inläsning på Storytel.

Kjell Westö har jag fått tips om när det kommer till män som ifrågasätter mansrollen. Jag älskade hans bok Hägring 38 och när mina bokcirkelkompisar ville läsa hans helt nya Tritonus, var jag inte sen att haka på. Boken är utgiven på Förlaget och här i Sverige på Albert Bonniers förlag. Jag lyssnade på Kjell Westös egen inläsning på Storytel.

Jag har läst Edwidge Danticat bok Att skörda ben, som nyligen getts ut på

Jag har läst Edwidge Danticat bok Att skörda ben, som nyligen getts ut på